Sunday, September 14, 2008

clinical effects of es

Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS)

Sensory TENS (high-rate TENS)

Used mostly in acute phase of pain or postoperatively

Pain reduction due to spinal gate mechanism

Depolarization results in a tingling sensation

Desirable to avoid muscle contraction

Motor TENS (low-rate TENS)

To treat subacute pain or trigger points

Targets the motor pain modulation theory

Pain relief may be delayed in comparison to that with sensory TENS

Pain relief lasts longer than with sensory TENS

Noxious TENS

Pain relief through central biasing mechanism

Commonly used with point stimulators

Portable TENS

Units are battery operated and can be self-administered

Clinician presets phase duration and pulse rate

Interferential stimulation (IFC)

Used for pain relief, increased circulation, and muscle stimulation

Applies two medium-frequency currents simultaneously

Waveforms of the two are superimposed on each other, which causes interference

Interference creates a “beat” mode

Wedenski’s inhibition—cutaneous nerve inhibition

Sweep frequency—feature available on some units that causes a rhythmical frequency change to reduce accommodation

Uses four electrodes in a quadripolar configuration

Allows for centralized concentration of current

Maximized by electrode placement so that intensity is perceived in area of pain

Can be used with other modalities

Premodulated interferential method easier to set up, but differs slightly

Bipolar electrode configuration

Currents are mixed in the machine, not the tissues

High-voltage stimulation (HVS)

Must be able to transmit a voltage of at least 150 V

Must use a twin-peaked monophasic current

High peak, but low average current provides deep penetration of a comfortable current

Used for pain control, edema reduction, tissue healing, and reduction of muscle spasm

Key feature of this unit is ability to be used with appendage submersion treatments

Muscle reeducation

Neuromuscular electrical stimulation (NMES)

Goal of treatment is to elicit a strong muscle contraction through stimulation of the alpha motor nerve

Can be used to slow disuse atrophy in innervated muscle

Assists neuromuscular function by enhancing force capacity (ability of muscle to contract) versus true “strengthening” of the muscle

Electrically produced contractions cause greater fatigue than physiological contractions

Duty cycle (rest time) must be imposed

Uses of galvanic current

Iontophoresis

Ions in solution are transferred through the intact skin via an electrical potential (like charges are repelled)

Uses DC generator

Most commonly used to suppress inflammation and pain

Treatment guidelines not well defined

Difficult to quantify amount of medication delivered into the tissues

Treatment should be physician prescribed

Safe application requires proper equipment and observation of cautions and contraindications

Direct stimulation of denervated muscle

Can occur secondary to trauma

Upper motor neurons—injury results in permanent paralysis; lower motor neuron is still intact and stimulation can still occur through the nerve

Alpha motor neurons—can regenerate, and active control of muscle can be restored

Electrical stimulation does not reinnervate, but maintains the contractile proteins in the muscle

Microcurrent

Effects and benefits

Evidence is limited

Only application shown to be effective is in treatment of slow-healing skin lesions

Summary

Electrical stimulation that crosses the skin to excite a nerve is considered TENS—transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation.

Many types of units are available to the clinician, allowing many parameters and waveforms to be manipulated in order to achieve a treatment goal.

The clinical uses of electrical stimulation include pain management, muscle stimulation for alpha motor nerve, stimulation of denervated muscle, iontophoresis, edema reduction, and wound healing.

Electrical stimulation in any form of TENS (sensory, motor, noxious, portable, and interferential) is used primarily for pain relief.

Neuromuscular electrical stimulation (NMES) is used primarily to reeducate muscle contraction of the strengthening muscle.

Iontophoresis is used primarily to decrease inflammation, pain, or both.

haemophilia

Page 1

ROADMAP FOR

MANAGING

PAIN

PASSP RT

to well-being

empowering people with bleeding disorders

to maximize their quality of life

Page 2

Roadmap for Managing Pain

The Canadian Hemophilia Society (CHS) exists to improve the quality

of life of persons with hemophilia and other inherited bleeding

disorders and to find a cure.

The CHS consults qualified medical professionals before distributing

any medical information. However, the CHS does not practice

medicine and under no circumstances recommends particular

treatments for specific individuals. In all cases, it is recommended that

individuals consult a physician before pursuing any course of treatment.

The CHS would like to acknowledge those people who contributed to

the development of Roadmap for Managing Pain.

Jenny Aikenhead

Physiotherapist, Alberta Children’s Hospital, Calgary, AB

Maureen Brownlow, RSW

IWK Health Centre, Halifax, NS

Nancy Dower, M.D.

Walter Mackenzie Health Sciences Centre, Edmonton, AB

Sophia Gocan, R.N.

Member, CHS National Programme Committee, Ottawa, ON

Ann Harrington, R.N.

St. Michael’s Hospital, Toronto, ON

Heather Jarman

Pharmacist, St. Joseph’s Health Care, London, ON

D. William C. Johnston, BMedSC, M.D., FRCS(C)

Orthopedic Surgeon and Site Medical Director of the University of

Alberta Hospital, Edmonton, AB

Peter Leung, M.D.

Pain Management Service, St. Michael’s Hospital, Toronto, ON

Pam Wilton, R.N.

Vice-President, Canadian Hemophilia Society

Clare Cecchini

Program Coordinator, Canadian Hemophilia Society

David Page

Blood Safety Coordinator, Canadian Hemophilia Society

Supported by Baxter BioScience

For further information please contact:

Canadian Hemophilia Society

625 President Kennedy Avenue, Suite 505

Montreal, Quebec, H3A 1K2

Tel:

(514) 848-0503

Toll Free: 1-800-668-2686

E-mail:

chs@hemophilia.ca

Website: www.hemophilia.ca

Note: Bleeding disorders affect both men and women.

The use of the masculine in this text refers to both.

ISBN 0-920967-50-7

Page 3

Roadmap for Managing Pain

1

Table of Contents

Introduction ......................................................2

The impact of pain on the family......................2

Pain – the fifth vital sign....................................4

The role of the comprehensive care team in

pain management............................................6

Advocating for better pain management ........7

The use of analgesic..........................................8

Physiotherapy –

another approach to pain management ........9

Orthopedic and surgical management of pain ..11

Complementary and alternative approaches

to pain management ....................................12

Conclusion ......................................................14

Resources ........................................................14

Page 4

2

Roadmap for Managing Pain

INTRODUCTION

“It is difficult to convey how chronic pain totally invades

and affects all aspects of your life. It is a constant

inescapable entity. And it is difficult to make others

understand. Everyone has endured pain, but not the kind

of pain that you must live with 24 hours a day, 7 days a

week, day and night.”

- a 50-year-old man with hemophilia

This eloquent statement was made by a person with

hemophilia interviewed during an informal survey on the

impact of pain.

It reinforces the message that pain experienced by people

with bleeding disorders is not well understood, assessed or

treated. Forty percent of the people interviewed reported

having pain all the time. Children also have pain and often

have difficulty describing the level of their pain. Many adults,

especially those with chronic joint damage, say that pain is

the major element affecting their quality of life. Yet it is only

recently that attention is starting to be paid to this serious

problem.

The most common reasons given for not taking medication

are that…

•

pain isn’t considered bad enough

•

side-effects are a problem

•

access to a pain specialist is difficult.

The goal of this booklet, Roadmap for Managing Pain, is

not to provide all the answers on pain management. Rather,

it is intended as a guide, showing some of the different routes

to take, some of the signposts along the way and, hopefully,

destinations which provide some comfort and relief.

Just as importantly, it aims to encourage open discussion

of pain and to help people realize that suffering in silence is

not the best way to cope.

THE IMPACT OF PAIN ON THE FAMILY

People who live with hemophilia

and other bleeding disorders are

veterans in the acute care of bleeds.

They are, however, strangers in the

uncharted waters of effective pain

management. For many years, pain

has been seen as an unavoidable

part of the condition—something to be suffered, often alone

and in silence.

Often, people are reluctant to complain. They have built

an arsenal of weapons to deal with pain, including doing their

best to ignore it. There are signs, however well a person

hides it, that a person is dealing with pain, for example…

Page 5

3

Roadmap for Managing Pain

•

mood changes

•

a reluctance to communicate and interact

with others

•

increased irritability

•

inability to concentrate

•

difficulty sleeping

•

a decreased interest in favourite activities

•

a lack of appetite.

“My pain has progressed significantly in the last few years.

It has an impact on most aspects of my life. My ability to

climb stairs, walk distances (especially on uneven ground),

type at the computer, hammer a nail and open a jar, to

mention only some examples, have all been affected.

On days when the pain is extreme, it can have a negative

impact on my mood and it affects those around me.”

– a 35-year-old man with hemophilia

In the longer term, ineffective pain management may lead to…

•

missing school or work

•

missing out on social and family activities

•

feelings of futility and hopelessness.

Pain is an almost invisible presence. Yet it casts a net

beyond the person who is directly affected. In fact, pain has

never been suffered alone. Family members have always been

aware of the suffering, although limited in their resources to

deal with it. They are affected by the pain of a family member

in a number of ways—emotionally, socially, academically, finan-

cially and spiritually—depending on the family situation of the

person with the bleeding disorder.

“When I’m in pain, I tend to express it by complaining

verbally—to tell the truth, by screaming. My family

doesn’t like to see me suffer and they do their best to

comfort me and distract me. My mother gives me my

Niastase and also morphine for the pain if necessary.

My sister tries to watch TV with me. My father talks to me

about hunting and fishing, which I’m crazy about, and we

often look at magazines together.”

– a 13-year-old boy with a factor IX inhibitor

Families in the bleeding disorder community have

developed ways of dealing with the condition by…

• educating themselves about their particular

situations

• being open in working with the members of

the comprehensive care teams

• learning to do home treatments

• developing internal strengths

• being creative in dealing with problems

• maintaining a sense of hope for the future.

These positive coping abilities now need to be

applied to the new frontier of pain management.

Page 6

4

Roadmap for Managing Pain

PAIN – THE FIFTH VITAL SIGN

Most health care providers and patients are used to having

the four routine vital signs— blood pressure, pulse rate,

temperature and respiratory rate—recorded at every

assessment. Yet the most common reason for seeking medical

care is pain. In 1995, the term, “fifth vital sign”, was coined,

suggesting that that pain must be measured and treated.

What then is pain? A medical definition is: “An

unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated

with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms

of such damage.”

A person with hemophilia, however, describes pain in

these words.

“I experience pain daily. It can be mild or severe. It can

be relentless. It can sometimes be unpredictable.

I associate my pain with an imaginary companion I like to

call the dragon. This dragon travels with me all day,

every day. He makes it his point to remind me when I am

doing something destructive by breathing his heat and

making me uncomfortable. As I like being active, I would

hate to see the trouble I might get into if I could silence

this dragon completely.”

- a 35-year-old man with hemophilia

Pain in hemophilia is usually of two types:

Acute pain is usually due to bleeding into joints and

muscles and, more rarely, the after-effects of surgery.

Chronic pain is associated with joint degeneration or other

long-term complications of hemophilia.

Pain is always subjective—it is the person with pain who

decides if there is pain or not—and always unpleasant. And

it is an emotional experience. When pain becomes chronic,

the actual injury, and even the physiological responses, may

not be visible.

Why assessing and managing pain is so important

There are many roadblocks to the humane and competent

assessment and management of pain.

• Patients and health care providers often differ

culturally and socially.

• Treatment for chronic pain may be unavailable,

unaffordable or not covered by health insurance.

• The variability and unpredictability of pain in people

with bleeding disorders may lead to an adversarial

relationship between patients and health care providers.

Page 7

5

Roadmap for Managing Pain

Recognizing pain as the fifth vital sign puts assessment at

the forefront, and allows the patient and family to create an

alliance with the health care providers against suffering.

The aim of pain control within the first few hours of a

bleeding episode is relief of suffering. Unrelieved pain can

actually interfere with healing and turn acute pain into a

chronic problem.

With chronic pain control there is the added aim of

maintaining daily function. The final goal is a balance

between the efficacy of pain relief, the side effects if any,

and being as functional as possible.

All modalities of pain management—physical,

pharmacological and psychological—should be incorporated

into the therapeutic plan, if beneficial. Then, there is no fear

of the agony of the next episode because the patient can

assume “control”, and knows back-up plans are in place.

Fortunately, there is already a major shift in attitudes

toward pain medications. Not so long ago, there was a

reluctance to prescribe pain killers because they might cause

addiction or interfere with recovery. Research has shown that

the risk of clinical addiction is overestimated and, in fact,

quite rare at the dosages used for pain management. What’s

more, recovery takes place faster when pain is properly

managed.

How pain is measured

Unlike its vital sign counterparts, there is no gadget to

measure pain—it must be evaluated by asking questions

and observing behaviour. These are some helpful tools:

For children aged 3 and older, a range of tools is avail-

able for self-reporting and behaviour observation; children

from approximately age 5 are able to reliably complete a

VAS (Visual Analog Scale) score. One useful tool might be

the “Face Scales”.

Pain has sensory, emotional, motivational, cognitive, and

behavioural dimensions. Hence the individual’s subjective

response must override the clinician’s bias. Every patient

deserves the most effective treatment, not what the

provider feels he/she should have.

Page 8

Roadmap for Managing Pain

6

THE ROLE OF THE COMPREHENSIVE

CARE TEAM IN PAIN MANAGEMENT

In various ways, all of the comprehensive care team

members are involved in the assessment and management

of pain.

The person with the bleeding disorder and, in the case

of a young child, his/her parents, are at the centre of the

process. They need to be able to recognize bleeds early

and know the difference between pain from acute bleeds

and from chronic conditions.

“I now know I have to get treatment as soon as possible

when I think I am bleeding. Sometimes I think I can get

away without treatment and I wait before telling my

mother. This is often how the pain gets very bad…

but not always.”

- an 8-year-old boy with hemophilia

The nurse coordinator can ensure that pain is assessed

and treated by the appropriate team member. In

managing both acute and chronic pain, good bleed diaries

are most helpful. So are pain diaries to record preceding

events, intensity of pain, activity level, interventions and

response to treatment.

The hematologist can develop a management plan for

both acute and chronic pain which could include

medication. If you do not live close to the Hemophilia

Treatment Centre (HTC), your family physician will need to

be involved. In some parts of Canada, HTCs are located in

large health centres, which include pain management

teams whose members have specialized knowledge in the

management of all aspects of pain.

The physiotherapist can make various recommendations

for treating acute or chronic pain. The overall goal is to

prevent secondary complications due to pain, such as tight

musculature or poor mobility.

The social worker can help the patient manage the life

complications that occur due to pain.

Comprehensive care teams in pediatric and adult

centres often have close working relationships with

rheumatology and orthopedic teams whose expertise can

be called upon to treat pain. Treatments such as joint

injections, synovectomies or joint replacements are some

of the options.

People with pain, and their families, need to be aware

that pain is a manageable condition. It doesn’t need to

be suffered in silence.

Discuss it with your

clinic team and work

out a plan that suits

you.

ADVOCATING

Page 9

Roadmap for Managing Pain

7

FOR BETTER PAIN

MANAGEMENT

“My physician told me she never realized how much

pain people with hemophilia had until she went to a

CHS workshop on pain management. She couldn’t

believe how well her patients hid the pain.”

- a 50-year-old man with hemophilia

Advocacy is a process of promoting a cause on behalf of

oneself and/or others. An advocate is someone who works

through that process.

You are your own best advocate but, depending on the sit-

uation, the role of advocate can be played by almost anyone.

•

a family member—spouse, parent or sibling—

or close friend

•

a nurse, especially the nurse at the HTC

•

a physiotherapist

•

a social worker.

The HTC is part of a network of clinics across Canada and

therefore the comprehensive care team has an established net-

work of expertise it can tap into for help in difficult situations.

You may need to seek help from experts in the field of pain

management. It is sometimes difficult to get a referral to a

specialist because many people, including physicians, simply

do not understand the extent of the pain. In addition to the

hematologists at the HTC, a family physician can also facilitate

a referral. It is always preferable to have your family physician

and/or your hematologist working with you. So, in all likeli-

hood, you will need to convince these people of your need for

expert help.

Fatigue, immobility, frustration and anger are common in

patients with chronic pain, making it difficult to communicate.

When pain persists, confidence and respect for health care

professionals can quickly erode.

Effective advocacy can help you communicate competently in

a calm, yet assertive way, working with health care providers to

develop an effective pain management plan.

Effective communication strategies

Take a buddy - A family member or a friend who knows your

situation well can help you to have confidence and to be more

open about your situation.

Prepare ahead - Write down key points before the visit.

Be knowledgeable - Be ready to provide information about

your pain. Use resources such as this booklet to know your

options.

Be proactive - Ask to discuss your pain management. Propose

a solution if you think you have one.

Speak up! Be assertive! - State what the problem is and what

concerns you have. It won’t always help to “grin and bear it”.

Page 10

8

Roadmap for Managing Pain

Listen - Listen carefully to what the physician says. Don’t be

afraid to ask him to explain if you’re not sure you understand.

Stay calm - You may feel frustration and impatience because

of the pain. Staying calm can be difficult, but it is important.

Repeat yourself if necessary - If you find your concerns are not

getting addressed, calmly repeat your problem and insist that

you are serious about finding a solution.

Be polite and courteous, yet firm - The health care providers

are trying to do their jobs to the best of their abilities, but may

have little experience treating chronic pain.

Focus on the problem, not the people - You want relief from

pain—that is the problem at hand. Focus on finding a solu-

tion, and not on any difficulties you are having getting help.

Use “I-statements,” not “you-statements.” - Focus on how you

feel and what you need, not on any disputes with health care

providers.

THE USE OF ANALGESIC

“I never considered myself one to take drugs

to manage pain, at least not in the obvious

sense like taking Tylenol, because I rarely do

this. But I do have a strategy and do in fact take drugs

to manage my pain. I infuse with clotting factor on a

prophylactic basis to prevent bleeds and thereby prevent

episodes of pain. I take Celebrex®, not everyday as I

should, but when I start to feel constant nagging pain

or know that I will be involved in activity the next day.”

- a 35-year-old man with hemophilia

Most patients with acute pain can obtain relief with the

careful use of common drugs such as acetaminophen

(Tylenol®) or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

The new COX-2 inhibitors (Celebrex®, Vioxx®) have less

effect on platelet function than ibuprofen, which was often

used for patients as the NSAID of choice. The addition of opi-

oids, such as morphine, can increase the control of severe

pain, depending on the individual patient.

If oral medication is ineffective, intravenous (IV) therapy is

an option. Opioids can be given by IV bolus, or by continu-

ous administration for even more control.

“At the hospital the pain management team put me on

a pump so I could administer extra doses of morphine

myself when I felt pain. I didn’t have to ask for and

wait to get my painkiller. It was also very useful when I

started to move around again with the help of my phys-

iotherapist. I manage my pain and can do my exercises

better.

- a 13-year-old boy with a factor IX inhibitor

Page 11

9

Roadmap for Managing Pain

Many people worry that opioids are addictive or could

lead to abuse. While there are no guarantees against this,

physicians take all possible precautions. As long as the

amount used is for pain, then the chance of addiction is

quite low. Short-term use for acute bleeds or surgery is

very unlikely to lead to addiction.

Addiction is not the same as tolerance. When people

use opioid pain medication, their bodies become accus-

tomed to the dose. One may need to increase the amount

to get the desired effect. Changing to a different medica-

tion can sometimes avoid the increase.

Poorly treated pain is detrimental to patients. Poor pain

management produces abnormal pain behaviour and may

even cause patients to seek out street drugs because they

are afraid of not being able to manage severe pain.

Marijuana is probably better to reduce nausea, improve

appetite and promote sleeping. Its use must be individual-

ized. For most patients it is not the magic drug. Legal

access to marijuana is difficult.

When the patient is traveling, the physician can provide

a specific letter detailing the medications and the amount

needed. He/she may even set out a suggested plan of

medication for mild and severe bleeds. This will help the

physician in another city to manage the pain. It will also

provide evidence at borders that a person is authorized to

carry these medications.

There are many useful medications for controlling pain.

In all cases, the type of analgesic and the route of adminis-

tration must be tailored to the individual patient. What’s

more, the underlying health problem must be managed by

knowledgeable health care workers.

PHYSIOTHERAPY – ANOTHER

APPROACH TO PAIN MANAGEMENT

The Pain Service at the Hospital for Sick Children always

recommends appropriate exercise to our patients. We

know that exercise makes the body release chemicals,

called endorphins, that not only make us feel less pain,

but also make us feel good. It’s something you can

control and do for yourself.

- Dr. Michael Jeavons, Psychiatrist,

Hospital for Sick Children’s Pain Service

An exercise or fitness program improves…

• Muscle strength - Stronger muscles tire less easily, which

results in extra support and protection for the joint and

reduces the stress and strain that can cause pain.

• Joint range of motion - Improved mobility of the joint

results in better alignment of the joint and decreased stress

on its surrounding structures. Exercises help reduce

stiffness and, by improving movement, may alleviate pain.

Page 12

10

Roadmap for Managing Pain

• Flexibility - Joint contractures and/or muscle

shortening may result in pain. These respond

well to stretching exercises. Improved flexibility

also decreases the chance of muscle bleeds.

• Coordination and balance - The development

of these skills results in a quicker response to a

sudden movement and a decreased chance of

further injury to the joint.

• Confidence and peer acceptance - Exercising

allows sharing with friends. Participation and

success bring confidence.

• Feelings of well-being and decreased anxiety -

Mental stress and anxiety are known to influence

sleep patterns, muscle spasm, the frequency of

bleeds and increase sensitivity to pain. Exercise

can decrease feelings of stress.

• Release of endorphins - Endorphins are natural chemicals

produced by the body and act as a damper to the

sensation of pain. Their production is thought to be

influenced by exercise, heat, cold, positive attitude, some

physiotherapy electrical modalities, relaxation and

medications.

• Endurance and weight loss - Cardio-vascular exercises

increase endurance and strength and therefore reduce

stress on the joints. Weight loss may occur, which also

decreases pressure on the joint surface.

“Sometimes applying ice helps a bit. I have several

orthotics I can use to immobilize the affected joint if

the bleeding is in the joint. I also use crutches or my

wheelchair when I have to. Because I had many

hemorrhages, I didn’t go to school for a few years.

I have been back at school since September 2002 and

I love it. I have a lot less bleeding because I am more

active and my muscles are stronger.”

- a 13-year-old boy with a factor IX inhibitor

A physiotherapist at the HTC can assess the pain and

assist in choosing an exercise or activity program. Ask the

physiotherapist about these other ways to reduce pain.

• Non-electrical treatments such as hot packs, ice,

hydrotherapy, splinting, foot orthotics and acupuncture

• Electrical modalities such as Transcutaneous Electrical

Nerve Stimulation (T.E.N.S.) and ultra-sound

Recommended activities for people who suffer from the

pain of arthritis related to hemophilia are those that have

low impact on the joint but allow mobility, strengthening and

cardio-vascular exercise. They include:

•

swimming and aquacise

•

T’ai Chi

•

yoga

•

bicycling

•

walking, dancing, bowling and hiking.

Page 13

11

Road for Managing Pain

For more information, see the Passport to Well-Being

module entitled: Destination — Fitness.

ORTHOPEDIC AND SURGICAL

MANAGEMENT OF PAIN

Orthopedic interventions can be very effective in managing

pain. Acute pain from recurrent bleeding into target joints can

be helped by procedures such as synovectomy. Chronic pain

from an irrevocably damaged joint can be relieved by

procedures such as joint replacement. All invasive procedures

must be performed under the protection of factor

replacement. The hemophilia doctor must be involved to

ensure that adequate levels of replacement are provided for

the appropriate time post-operatively. Factor replacement

may be recommended prior to post-operative physiotherapy

sessions.

Synovectomy

Removal of the swollen synovium (synovectomy) can

decrease recurrent bleeding into a target joint and

reduce pain. Three techniques can be used:

Radioactive synovectomy - A radioactive isotope is

injected into a target joint. Within the joint, the

radioactivity reduces the amount of swollen synovium.

Arthroscopic synovectomy - Using small surgical

incisions a tiny camera is inserted into a joint to guide the

removal of the synovium through the other incisions. This can

be used for ankles, knees and elbows.

Open synovectomy - The joint is opened surgically and the

synovium removed.

Joint replacements

Chronic joint damage produces pain and decreased range

of motion. When the pain is severe and interferes with the

activities of daily living, joint replacement is an option. Knee

and hip replacements are the most common. Elbow, shoulder

and ankle replacements are done less commonly due to the

complexity of the joints.

Before the elbow replacement in 1999, I was in

tremendous pain continuously for a period of about

8 months to the point of having to stop working.

– a 49-year-old man with hemophilia

The damaged joint and adjacent bone are removed and

replaced with plastic and metal components (knee) or with a

metal ball and a plastic cup (hip). Pain control is critical during

the recovery period so that early mobilization and physiothera-

py can occur. Most people are left with a pain-free joint.

Page 14

Roadmap for Managing Pain

12

Other surgeries

Other surgeries that might be considered to manage pain

from damaged joints are:

• Removal of small bony growths around the joint margins

(cheilectomy)

• Fusion of the joint to leave a painless immobile joint

(arthrodesis)

• Removal of the radial head to improve rotation of the

forearm

• Removal of the ball part of the femur to allow a fibrous

union to develop. This may be done if a hip replace-

ment fails

• Removal of a wedge of bone from the femur or tibia to

realign the leg and reduce pain (osteotomy).

Less invasive options

Injection of a corticosteroid into an affected joint can be

used in the short to medium term to decrease inflammation

and pain. This could be used while awaiting surgery.

“Ultimately, the operations—replacements and

fusions—were godsends and did relieve the pain. I

do not run or skate and I avoid stairs like the plague,

but my wife and I play golf—I still have a slice—and

I am able to enjoy travel and visit family and friends.”

- a 43-year-old man with hemophilia

COMPLEMENTARY AND ALTERNATIVE

APPROACHES TO PAIN MANAGEMENT

“When I’m at home, I find that my dog helps me a lot

to manage my pain. I see a huge difference since he

became part of our lives. ”

- an 8-year-old boy with hemophilia

Complementary and Alternative Health

Care (CAHR) are therapies that are

considered outside of mainstream medical

practices.

A complementary therapy, such as

aromatherapy to help lessen a person’s

discomfort following surgery, is used together with

conventional medicine. In contrast, alternative medicine, such

as a special diet to treat cancer instead of undergoing surgery

that has been recommended by a conventional doctor, is used

in place of conventional medicine.

While there is scientific evidence supporting some CAHC

therapies, for most there remain unanswered questions

regarding safety and effectiveness. As these therapies

become better understood and validated with sound scientific

research, some CAHC therapies will become integrated into

traditional medicine.

Page 15

Roadmap for Managing Pain

13

Types of complementary and alternative health care therapies

CAHR therapies can be divided into five categories, or

domains:

• Alternative medical systems including homeopathy,

naturopathy, traditional Chinese medicine and

Ayurveda

• Mind-body interventions including patient

support groups, meditation, prayer, biofeedback,

humour therapy, and therapies that use creative

outlets such as art, music or dance

• Biologically-based therapies using substances

found in nature, such as herbs, foods, and

vitamins

• Manipulative and body-based methods

including chiropractic or osteopathic manipulation,

reflexology and massage

• Energy therapies including qi gong, Reiki and

Therapeutic Touch.

The value of complementary and alternative health care

therapies in reducing pain

It is important to ask yourself what you expect from CAHC

therapies. While you may not be able to find relief for your

pain, some CAHC therapies may be able to provide you with

indirect benefits.

Consider the potential benefits before starting a treatment.

Monitor how you feel as a result of the treatment. Then make

a decision about whether to continue it.

The safety of complementary and alternative health care

therapies

To protect yourself from potential risks involved when using

CAHC therapies, be sure to:

• Discuss all of your CAHC practices with your physician

and other health care providers. Ensure the therapy you

are considering will be safe when taking into account your

current health status.

• Try to gather information from sources that look at both

sides of a therapy—those who oppose and those who

support the therapy. Consult publications and web sites

that stem from governments, recognized medical

organizations, well-known scientific sources or academic

institutions.

• Be cautious about any of the claims that you come

across.

• Seek out only fully competent and licensed practitioners.

Ask individuals about their training and experience. Check

with provincial or territorial Ministries of Health.

Page 16

Roadmap for Managing Pain

14

Some CAHC products contain powerful pharmacological

substances which can be toxic on their own, or when used

with other medications. Some can affect the ability of your

blood to clot. This is especially dangerous for a person with a

bleeding disorder. Some substances known to negatively

affect clotting are…

•

black cohosh

•

cat’s claw

•

feverfew

•

garlic

•

ginkgo biloba

•

pau d’arco.

CONCLUSION

For many, the pain of acute bleeding is the most vivid

memory of living with a bleeding disorder. Thanks to better

treatment, such episodes are much rarer today, but still a

reality, especially for those with an inhibitor. The long-term

consequences of bleeding, however, mean that many adults

are living with damaged joints and

the burden of chronic pain. For

many years, this pain went largely

unrecognized or was accepted as

unavoidable. Today, we know a

roadmap for pain management

must be drawn so that people can

find their way to some relief.

RESOURCES

1. Pain – The Fifth Vital Sign, Canadian Hemophilia Society, 2004,

www.hemophilia.ca

2. The Pain Management Book for People with Haemophilia and Related

Bleeding Disorders, Hemophilia Foundation Australia and the World

Federation of Hemophilia, Treatment of Hemophilia Series, Number 22,

April 2000, www.wfh.org

3. All About Hemophilia – A Guide for Families, Canadian Hemophilia Society,

2001, www.hemophilia.ca

4. Hemophilia Today, Canadian Hemophilia Society, www.hemophilia.ca

5. Handbook for Physical Activity Guide, Health Canada, www.hc-sc.gc.ca

6. Health Canada’s Office of Natural Health Products, www.hc-sc.gc.ca

7. Canadian Health Network, funded by Health Canada, www.canadian-health-

network.ca

8. Canadian Health Portal, links to provincial or territorial Ministries of Health,

www.pcs-chp.gc.ca

9. NCCAM, the U.S. Federal Government’s lead agency for scientific research

on complementary and alternative medicine, www.nccam.nih.gov

Sunday, August 24, 2008

Saturday, August 23, 2008

Saturday, March 29, 2008

BACK CARE PILATES EXERCISE

Pilates is another great exercise for relieving back pain because it focuses on strengthening your core muscles, which include the back.

Pilates exercises are very smooth and controlled movements, so there is little danger of getting injured while exercising. It’s also a great way work on your strength and flexibility, both of which help to alleviate back pain. . One of the best benefits of Pilates is that it helps improve posture, a common cause of lower back pain.

The following Pilates exercises benefit the spine and are appropriate for beginners. Do each exercise slowly and smoothly, and repeat ten times if you can. The key to pilates is quality of exercise, not quantity; it is more important to do fewer exercises slowly and correctly than to do all ten repetitions quickly.

THE HUNDRED:

Start by lying on your back with your legs either stretched out or bent at the knees, whichever is most comfortable. Raise your head and, if you can, your legs off the floor a few inches. If this puts too much stress on your lower back, just raise your head and keep your feet on the floor with your knees bent. Try to keep your neck relaxed. Now extend your arms, and raise and lower them about two inches. While doing this, inhale for a count of five and exhale for a count of five.

Sit with legs extended in front of you and slightly more than hip width apart and feet flexed. Inhale and pretend that you are hovering over an imaginary beach ball by leaning your upper body forward, arms extended, while rounding your back and pulling in your abdomen. Exhale as you sit back up slowly one vertebra at a time.

The ROLLUP:

Begin by lying on your back, legs extended, and arms stretched above your head with your shoulders on the floor. Alternately, you may want to do this exercise with your feet on the floor, knees bent. Inhale

and lift your arms toward the ceiling. Exhale and roll your torso forward, as if you are doing a full body sit-up. You should ideally roll into a sitting position, but if you can’t, just bring your torso as far off the mat as you comfortably can before returning to your starting position.

The SAW: Sit with your legs slightly wider than hip width, feet flexed. Your arms should be extended straight out to the side. Sit up very straight as if you are trying to touch the ceiling with the top of your head. Exhale; turn your body to the left, keeping your arms in line with your shoulders, and bend over as if your hand is going to saw off your little toe. Inhale, return slowly to your original position, and repeat on the other side.

The SAW: Sit with your legs slightly wider than hip width, feet flexed. Your arms should be extended straight out to the side. Sit up very straight as if you are trying to touch the ceiling with the top of your head. Exhale; turn your body to the left, keeping your arms in line with your shoulders, and bend over as if your hand is going to saw off your little toe. Inhale, return slowly to your original position, and repeat on the other side.

SPINE TWIST: Sit with your legs slightly more than hip width apart and your arms extended out to the sides. Inhale, tighten your abs, and sit up very straight as if you are trying to touch your head to the ceiling. Now exhale and turn to the right as far as you comfortably can. This exercise is to increase your back mobility only, so do not stretch your back muscles. Inhale and return to your starting position. Repeat on the left side.

Leg Circle with fit band

Leg Circle with fit band

1. Start by lying on your back and placing a band around the foot that is pointed towards the ceiling.

2. Holding the other end of the band with your hands allow your leg to fall towards the side.

3. Once your leg reaches the side then bring it back up to the top and let your leg fall toward the other foot.

4. Bring your leg back up and finish by shifting the leg to the other side.

5. Return to the starting position and repeat.

Pilates Saw on Stability Ball

1. Sit on stability ball with your legs straight and your arms outstretched to the side.

2. Rotate and twist your trunk so that your right hand reaches and touches your left foot.

3. Return to t he starting position and repeat to the other side.

he starting position and repeat to the other side.

Prone Single Leg Kick

1. Lie face down on the floor and legs straight.

2. Slowly curl one leg up until your foot hits your hip.

3. Return to the starting position and repeat with the other side.

Scissors

Scissors

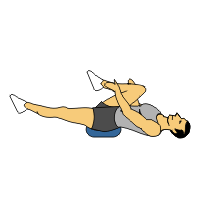

1) Start position: Straighten both legs so that they are perpendicular to floor.

2) Slowly lower one leg to approximately 45°.

3) Return to start position and repeat.

4) Remember to maintain stability in lower back throughout movement by keeping abdominal muscles contracted - DO NOT ARCH LOWER BACK. To increase intensity, lower legs past 45° without touching floor as long as trunk stability is maintained

Thursday, March 20, 2008

What is a Active Cycle of Breathing Techniques?

The Active cycle of breathing techniques (ACBT) is a simple pattern of breathing to -

loosen and clear secretions

improve ventilation

This leaflet is intended to remind you what you were taught by your Physiotherapist.

The parts of the ACBT are -

This is normal gentle breathing using the lower chest, with relaxation of the upper chest and shoulders. It helps you to relax between the deep breathing and huffing.

Deep breathing :

These are slow deep breaths in followed by relaxed breaths out. 3 - 4 deep breaths are enough.

Huffing :

This is a medium sized breath in, followed by a fast breath out through an open mouth, using the muscles of the chest and stomach to force the breath out.

This will move secretions along the airways to a point where you can cough them up.

Coughing :

This should follow 2 - 3 huffs OR a deep breath in.

Don't cough unless secretions are ready to be cleared.

Active cycle of breathing :

This is a flexible technique and can be varied to suit you

In what position should I practice this breathing technique?

You can use this method of breathing in whatever position you find is most comfortable, or seems to clear most secretions, for example, sitting in a chair, lying on your side, or 'tipped' if this helps.

What other techniques can use with the Active Cycle of Breathing (ACBT)?

It is often beneficial to 'hold' for a second or two at the end of one or all of the deep breaths.

If your physiotherapist advises, you (or a helper) can 'clap' your chest while you breathe out.

How often should spend doing it?

If you have a chronic respiratory condition but you are very well, 10 minutes will be long enough to ventilate your lungs and clear any secretions.

You can do it as long as you are clearing any secretions but 20 minutes is usually long enough for any one treatment.

If you have an infection and your cough is more productive than usual, you will need to practice the cycle more often during the day.

Good luck - this is one very positive way that you can influence your own health.

Wednesday, March 19, 2008

Chest physiotherapy (CPT) is a technique used to mobilize or loose secretions in the lungs and respiratory tract. This is especially helpful for patients with large amount of secretions or ineffective cough. Chest physiotherapy consists of external mechanical maneuvers, such as chest percussion, postural drainage, vibration, to augment mobilization and clearance of airway secretions, diaphragmatic breathing with pursed-lips, coughing and controlled coughing